Rose Ann tossed and turned, puzzled by the intense itch in her eyes that had persisted for the past week. Other perplexities drifted through her mind as she lay awake on the stiff, bare-wire metal cot that she had grown accustomed to, stewing on her perceived shortcomings of Kenyan culture: “Why do the women let men treat them like slaves? Why don’t parents keep flies out of their baby’s eyes and mouth?” This wasn’t her first time to ponder, or to experience discomfort. Her past three months living in Ngararia exposed her to infected flea bites, food scarcity, a culture of men dominating women, etc. She eventually drifted off to sleep, until the chickens that slept under her cot began to cluck and crow early in the morning.

The next day happened to be the one time in Rose Ann’s stay that another Westerner travelled to the remote village. Berkeley Hackett—an American missionary—was sent by Rose Ann’s father to help her renew her visa. He took Rose Ann to Nairobi, where they visited the hospital. She was diagnosed with tropical trachoma (the leading cause of blindness in the world) and was prescribed eye salve, an analgesic, and strong antibiotics. Berkeley’s family hosted her for a week and assisted her recovery. It was refreshing, yet a bit strange, reacclimating to a Western-style home after assimilating with the East African way of life for a few months.

Known as “Maua” (flower), Rose Ann returned to Ngararia and joyfully greeted Hannah in Kikuyu, “Wemwega! Macho yangu wanapona” (Greetings! My eyes are healing). She soon got busy helping with the daily chores. In the small, smoke-stained dirt kitchen that doubled as Rose Ann’s bedroom, the two women began preparing ugali and sukuma wiki (greens) from the garden. Hannah had already made three treks to the local water hole to fill her jerry cans that morning, plugging the openings with a bud from a banana plant. She filled the cooking pot with water and started a wood fire under the three stones upon which the pot balanced. Rose Ann coughed as the hut filled with smoke, finally dashing outside to get some fresh air. Once the water came to a boil, Hannah gradually added some corn flour, stirring with a wooden paddle. After the meal was prepared, Hannah served her husband, and then the two women and Hannah’s child ate together in the kitchen. After lunch, Rose Ann swept the home with her “broom” (a handful of sticks), and used the remaining jerry cans, ashes, and leaves to scrub out the pots and dishes from the meal.

Several years earlier, while spending three years in Kenya as a teenager with her family, Rose Ann fell in love with the country and people. During her father’s missionary work from 1970–1973, two new disciples joined the Ngararia church plant: Joel Kago and Hannah Wangari, a newlywed couple in their twenties. Joel, a farmer by occupation, became a leader in the church. Hannah was a sweet, hardworking woman who was a friend to the Yoder girls. The couple were unable to have children, but when a neighbor birthed a child out of wedlock, they adopted the baby.

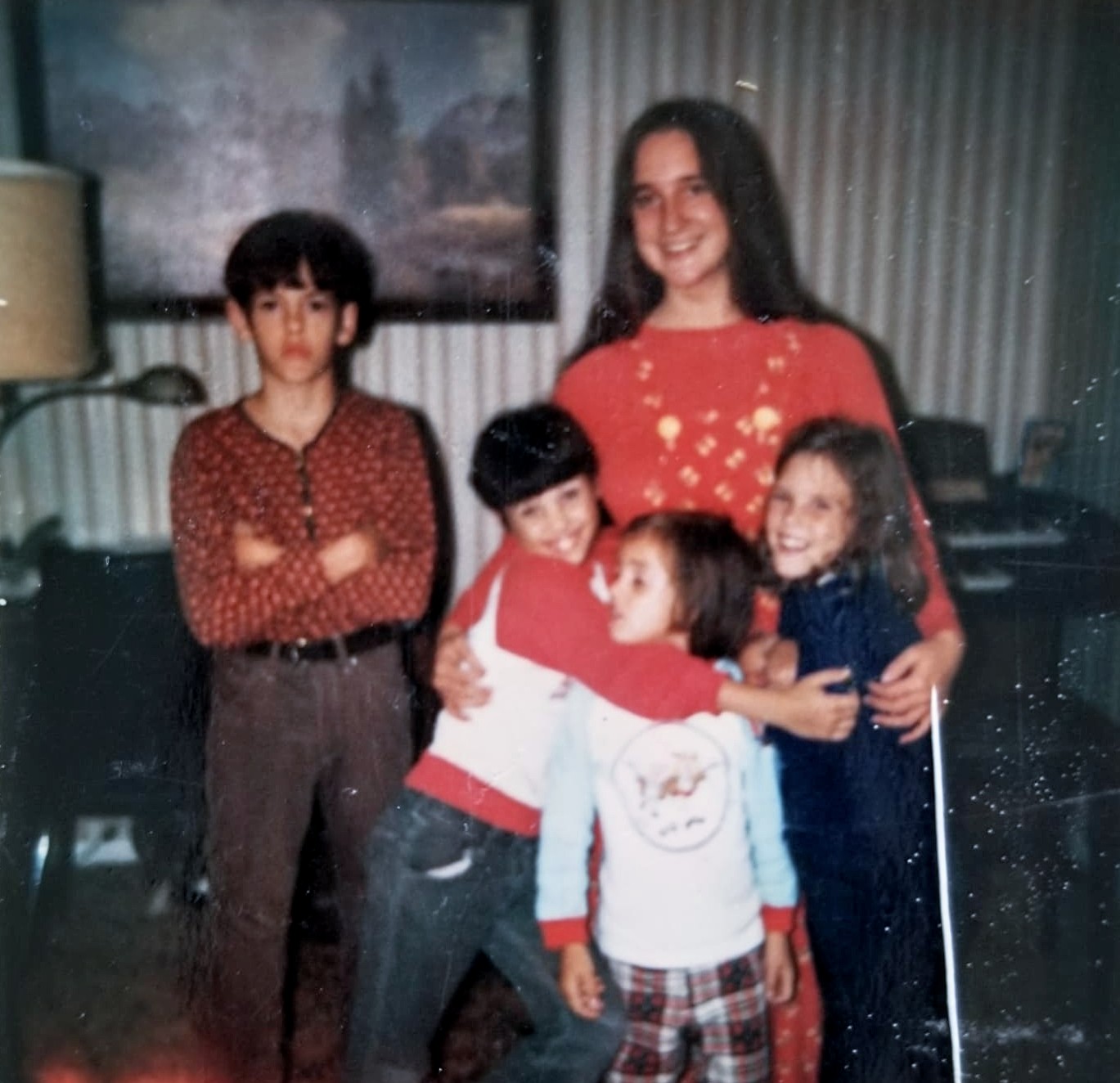

Rose Ann returned to the US as a recent high school graduate and got busy. She held several babysitting and home health care jobs, started a summer Bible club with the children in a neighboring trailer park, went evangelizing with her Bible at Zerns Farmers Market, had Bible studies with African American women in a Pottstown housing project, started dating, and was an active member in a local church. Alhough she was living a full life, she longed to get back to Kenya and diligently saved her earnings to that end. Her father then arranged for her to stay with the Kagos, so at age twenty-one she returned for six months. Carrying five changes of clothes, a bible, some notebooks, and a small amount of cash, she departed for Kenya in November, 1976.

For the first four months, Rose Ann lived with the Kagos in their mud hut. She immersed herself in the culture completely, acquiring fluency in Swahili and some Kikuyu. She proactively engaged with the women in the community. Every morning she would walk to a distant farm with her friend Regina to get cow milk for her baby. As they walked, they talked enthusiastically about heaven, and their love for Jesus. In the evenings Rose Ann visited Regina and her sister and their widowed mother, and they washed each other’s muddy feet in obedience to Jesus’ teachings—very practical in that culture as well. Rose Ann taught her friend Lucy praise songs translated into Kikuyu, and studied the Bible with her smiley friend Mary. She also accompanied Hannah on the long walk to the market in the distant town of Kandara, to sell her tomatoes.

After Rose Ann’s stay in Ngararia, a missionary from western Kenya connected her with Christian families from the Abaluhya, Luo, and Marigoli tribes. She spent a month staying with some of those families, learning about their cultures and participating in their fellowships. The final month she spent exploring the coast of Kenya from Mombasa to Pate Island, making exciting memories. Quintessential of her youthful, brash zeal, she once shouted down from a cliff, “You are evil!”, to an older white man who was skinny dipping with two prostitutes. He indignantly climbed up to where she was and asked, “And why am I evil?” All of these experiences at age twenty-one left her with a permanent yearning to be among the Kenyan people.

Here is an excerpt of Seth’s interview with Rose Ann:

Seth:

How did you get interested in working among the Kenyan poor?

Rose Ann:

I got a close-up experience of poverty. It didn’t even compare to poverty I saw in America—these were hardworking people who were barely surviving on the bare essentials. The Kagos would use corn cobs for fuel when firewood ran out. When beans and salt ran out they would only eat hard corn (supplies ran out seasonally because they were farmers). After not eating eggs for a month, I was thrilled when someone brought me two eggs. I gave them to Hannah to cook for me. She then split the meal between her, her husband, her baby, and me. In Africa, a gift to one is a gift to be shared with all. When I saw how hard-working and industrious they were and yet struggling so much, I realized they were the kind of people I’d really like to see helped. That poverty haunted me years after, keeping me up at night. I coined in my mind “the worthy, working poor.”

Seth:

What was life like where you stayed?

Rose Ann:

I tried to live just like them so that I wouldn’t be a source of envy. The bed they gave me was a fold-out metal cot with no mattress. I slept on the bare wires with a cloth. I drank their water—sourced from a dirty water hole, shared with livestock—and ate their food. My job was to sweep out the mud hut and compound with sticks and wash the dishes. I would also go on daily visits to women in the community. I didn’t help carry water because I thought the entire practice was demeaning towards women and didn’t want to support it. One time Joel got a stick and was beating Hannah relentlessly. A neighbor man had beaten his wife to death.

Seth:

Did you ever get sick?

Rose Ann:

The main time I got sick was when Hannah got offended by me saying the meat was rotten, so I ended up eating it. The only meat they had in a whole year was at Christmas time and they’d eat it even after a few days when it started spoiling because it was so rare. I also got trachoma, probably from sweeping the dust—the baby in the house would just pee on the floor and animals would come into the compound.

Leave a comment